-

Looking for HSC notes and resources? Check out our Notes & Resources page

Make a Difference – Donate to Bored of Studies!

Students helping students, join us in improving Bored of Studies by donating and supporting future students!

Challenging (?) Proof Question (1 Viewer)

- Thread starter CM_Tutor

- Start date

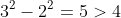

If one wanted to actually find examples of  , here is an approach that works for

, here is an approach that works for  .

.

I'll use the hyperbolic function and its inverse, which aren't in the MX2 syllabus but their definitions are quite simple to understand:

and its inverse, which aren't in the MX2 syllabus but their definitions are quite simple to understand:

) and

and )

Now, let

= x^n + \frac 1{x^n}) ,

,

be a real function where .

.

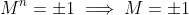

If is even, then

is even, then  = f(-x)) .

.

If is odd, then

is odd, then =-f(-x) ) .

.

That is, the parity of is the parity of

is the parity of  .

.

So without loss of generality, assume and make the substitution

and make the substitution  .

.

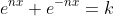

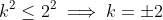

If = k) for some

for some  , then

, then

, so

, so

= \frac k2,)

.)

Since ,

,

.

.

We require , which should be expected, as

, which should be expected, as  \ge 2 ) for all positive

for all positive  .

.

The original proposition

is equivalent (I believe) to

\in \mathbb Z \implies 2 \cosh(nx) \in \mathbb Z ) .

.

We also find an interesting identity:

for all .

.

EDIT: It's worth noting that this shows that if , then

, then  .

.

If) then

then  .

.

The gap between the second and third perfect square is , and this gap will only increase as you go further out.

, and this gap will only increase as you go further out.

So . Subbing in these values confirms that

. Subbing in these values confirms that  .

.

I'll use the hyperbolic function

Now, let

be a real function where

If

If

That is, the parity of

So without loss of generality, assume

If

Since

We require

The original proposition

is equivalent (I believe) to

We also find an interesting identity:

for all

EDIT: It's worth noting that this shows that if

If

The gap between the second and third perfect square is

So

Last edited:

ewjfiwhelowaeoplg

New Member

- Joined

- Mar 30, 2020

- Messages

- 13

- Gender

- Undisclosed

- HSC

- 2020

Yes, strong induction is the standard X2 approach for these sorts of questions

There is one other possibility,Is the conditionreally necessary?

The only case of this I can see is, so it would be simpler to leave it unmentioned.

On reflection, the result is also true if the restriction on n is simply

I agree that the induction approach noted by ultra908 is the obvious / standard approach. The approach from fan96 is not one I had considered, but it's also beyond the MX2 syllabus. Are there any other approaches anyone would consider?

You could go into complex numbers and use Taylor series expressions for real and imaginary part, then you could prove local finite integer ABSOLUTE convergence from a point, calling z_n = M^n + M^(-n) and by proving that |Re(z_n)| and |Im(z_n)| ==> |z_n| converges. Type of approach from complex analysis.Prove that ifbut

, then

for all

.

I am curious as to how Extension 2 students would approach this as a proof problem, and wondering if there are other approaches beyond the two that occur to me.

Yes, it will work, but it is effectively a strong induction proof:Does my Binomial expansion not work, cus that and Induction is the only way My small brain can think off. was thinking of complex numbers too since its in that form but yeah haha

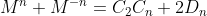

Now, applying the symmetry property that

Now, the last term in this series of sums depends on whether

Whether

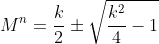

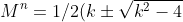

I was thinking about a proof like this: The quadratic equation with roots at  is

is

\big(x - M^{-1}\big) = 0) , which expands and rearranges to give

, which expands and rearranges to give x - 1)

It follows that

We then prove that , with or without using induction,

, with or without using induction,

because that gives must be an integer.

must be an integer.

It follows that

We then prove that

because that gives

Paradoxica

-insert title here-

This is completely valid but technically requires induction to complete the argument for all naturals.I was thinking about a proof like this: The quadratic equation with roots atis

, which expands and rearranges to give

It follows that

We then prove that, with or without using induction,

because that givesmust be an integer.

The logic is inductive, I agree, though it doesn't actually need to be presented as an induction proof.This is completely valid but technically requires induction to complete the argument for all naturals.